Karate

Web-Services Testing Made Simple.

Karate enables you to script a sequence of calls to any kind of web-service and assert that the responses are as expected. It makes it really easy to build complex request payloads, traverse data within the responses, and chain data from responses into the next request. Karate’s payload validation engine can perform a ‘smart compare’ of two JSON or XML documents without being affected by white-space or the order in which data-elements actually appear, and you can opt to ignore fields that you choose.

Since Karate is built on top of Cucumber-JVM, you can run tests and generate reports like any standard Java project. But instead of Java - you write tests in a language designed to make dealing with HTTP, JSON or XML - simple.

Hello World

Feature: karate 'hello world' example

Scenario: create and retrieve a cat

Given url 'http://myhost.com/v1/cats'

And request { name: 'Billie' }

When method post

Then status 201

And match response == { id: '#notnull', name: 'Billie' }

Given path response.id

When method get

Then status 200

It is worth pointing out that JSON is a ‘first class citizen’ of the syntax such that you can express payload and expected data without having to use double-quotes and without having to enclose JSON field names in quotes. There is no need to ‘escape’ characters like you would have had to in Java or other programming languages.

And you don’t need to create Java objects (or POJO-s) for any of the payloads that you need to work with.

Index

Features

- Java knowledge is not required and even non-programmers can write tests.

- Scripts are plain-text files and require no compilation step or IDE

- Based on the popular Cucumber / Gherkin standard, and IDE support and syntax-coloring options exist

- Syntax ‘natively’ supports JSON and XML - including JsonPath and XPath expressions

- Eliminate the need for ‘POJO’s or ‘helper code’ to represent payloads and HTTP end-points, and dramatically reduce the lines of code needed for a test

- Tests are super-readable - as scenario data can be expressed in-line, in human-friendly JSON, XML or Cucumber Scenario Outline tables

- Express expected results as readable, well-formed JSON or XML, and assert in a single step that the entire response payload (no matter how complex or deeply nested) - is as expected

- Payload assertion failures clearly report which data element (and path) is not as expected, for easy troubleshooting of even large payloads

- Embedded UI for stepping through a script in debug mode where you can even re-play a step while editing it - a huge time-saver

- Simpler and more powerful alternative to JSON-schema for validating payload structure and format that even supports cross-field / domain validation logic

- Scripts can call other scripts - which means that you can easily re-use and maintain authentication and ‘set up’ flows efficiently, across multiple tests

- Embedded JavaScript engine that allows you to build a library of re-usable functions that suit your specific environment or organization

- Re-use of payload-data and user-defined functions across tests is so easy - that it becomes a natural habit for the test-developer

- Built-in support for switching configuration across different environments (e.g. dev, QA, pre-prod)

- Support for data-driven tests and being able to tag or group tests is built-in, no need to rely on TestNG or JUnit

- Standard Java / Maven project structure, and seamless integration into CI / CD pipelines - with both JUnit and TestNG being supported

- Support for multi-threaded parallel execution, which is a huge time-saver, especially for HTTP integration tests

- Built-in test-reports powered by Cucumber-JVM with the option of using third-party (open-source) maven-plugins for even better-looking reports

- Easily invoke JDK classes, Java libraries, or re-use custom Java code if needed, for ultimate extensibility

- Simple plug-in system for authentication and HTTP header management that will handle any complex, real-world scenario

- Future-proof ‘pluggable’ HTTP client abstraction supports both Apache and Jersey so that you can choose what works best in your project, and not be blocked by library or dependency conflicts

- Mock HTTP Servlet that enables you to test any controller servlet such as Spring Boot / MVC or Jersey / JAX-RS - without having to boot an app-server, and you can use your HTTP integration tests un-changed

- Comprehensive support for different flavors of HTTP calls:

- SOAP / XML requests

- HTTPS / SSL - without needing certificates, key-stores or trust-stores

- HTTP proxy server support

- URL-encoded HTML-form data

- Multi-part file-upload - including ‘multipart/mixed’ and ‘multipart/related’

- Browser-like cookie handling

- Full control over HTTP headers, path and query parameters

- Intelligent defaults

Real World Examples

A set of real-life examples can be found here: Karate Demos

Comparison with REST-assured

For teams familiar with or currently using REST-assured, this detailed comparison can help you evaluate Karate: Karate vs REST-assured

References

- Karate a REST Test Tool – Basic API Testing - blog post and video tutorial by Joe Colantonio

- Writing BDD-Style Webservice Tests with Karate and Java - blog post and step-by-step tutorial by Micha Kops

- 10 API testing tools to try in 2017 - blog post by Christopher Reichert of Assertible

- Karate for Complex Web-Service API Testing - slide-deck by Peter Thomas

- Testing a Java Spring Boot REST API with Karate - a detailed tutorial by Micha Kops - featured on the Semaphore CI site

Getting Started

Karate requires Java 8 and Maven to be installed.

Maven

Karate is designed so that you can choose between the Apache or Jersey HTTP client implementations.

So you need two <dependencies>:

<dependency>

<groupId>com.intuit.karate</groupId>

<artifactId>karate-apache</artifactId>

<version>0.5.0</version>

<scope>test</scope>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>com.intuit.karate</groupId>

<artifactId>karate-junit4</artifactId>

<version>0.5.0</version>

<scope>test</scope>

</dependency>

And if you run into class-loading conflicts, for example if an older version of the Apache libraries are being used within your project - then use karate-jersey instead of karate-apache.

TestNG instead of JUnit

If you want to use TestNG, use the artifactId karate-testng. If you are starting a project from scratch, we strongly recommend that you use JUnit. Do note that dynamic tables, data-driven testing and tag-groups are built-in to Karate, so that you don’t need to depend on things like the TestNG @DataProvider anymore.

Use the TestNG test-runner only when you are trying to add Karate tests side-by-side with an existing set of TestNG test-classes, possibly as a migration strategy.

Quickstart

It may be easier for you to use the Karate Maven archetype to create a skeleton project with one command. You can then skip the next few sections, as the pom.xml, recommended directory structure and starter files would be created for you.

You can replace the values of ‘com.mycompany’ and ‘myproject’ as per your needs.

mvn archetype:generate \

-DarchetypeGroupId=com.intuit.karate \

-DarchetypeArtifactId=karate-archetype \

-DarchetypeVersion=0.5.0 \

-DgroupId=com.mycompany \

-DartifactId=myproject

This will create a folder called ‘myproject’ (or whatever you set the name to).

You can refer to this nice blog post and video by Joe Colantonio which provides step by step instructions on how to get started using Eclipse. Also make sure you install the Cucumber-Eclipse plugin !

Another blog post which is a good step-by-step reference is this one by Micha Kops - especially if you use the ‘default’ maven folder structure instead of the one recommended below.

Folder Structure

A Karate test script has the file extension .feature which is the standard followed by Cucumber. You are free to organize your files using regular Java package conventions.

The Maven tradition is to have non-Java source files in a separate src/test/resources folder structure - but we recommend that you keep them side-by-side with your *.java files. When you have a large and complex project, you will end up with a few data files (e.g. *.js, *.json, *.txt) as well and it is much more convenient to see the *.java and *.feature files and all related artifacts in the same place.

This can be easily achieved with the following tweak to your maven <build> section.

<build>

<testResources>

<testResource>

<directory>src/test/java</directory>

<excludes>

<exclude>**/*.java</exclude>

</excludes>

</testResource>

</testResources>

<plugins>

...

</plugins>

</build>

This is very common in the world of Maven users and keep in mind that these are tests and not production code.

With the above in place, you don’t have to keep switching between your src/test/java and src/test/resources folders, you can have all your test-code and artifacts under

src/test/java and everything will work as expected.

Once you get used to this, you may even start wondering why projects need a src/test/resources folder at all !

Naming Conventions

Since these are tests and not production Java code, you don’t need to be bound by the com.mycompany.foo.bar convention and the un-necessary explosion of sub-folders that ensues.

We suggest that you have a folder hierarchy only one or two levels deep - where the folder names clearly identify which ‘resource’, ‘entity’ or API is the web-service under test.

For example:

src/test/java

|

+-- karate-config.js

+-- logback-test.xml

+-- some-reusable.feature

+-- some-classpath-function.js

+-- some-classpath-payload.json

|

\-- animals

|

+-- AnimalsTest.java

|

+-- cats

| |

| +-- cats-post.feature

| +-- cats-get.feature

| +-- cat.json

| \-- CatsRunner.java

|

\-- dogs

|

+-- dog-crud.feature

+-- dog.json

+-- some-helper-function.js

\-- DogsRunner.java

Assuming you use JUnit, there are some good reasons for the recommended (best practice) naming convention and choice of file-placement shown above:

- Not using the

*Test.javaconvention for the JUnit classes (e.g.CatsRunner.java) in thecatsanddogsfolder ensures that these tests will not be picked up when invokingmvn test(for the whole project) from the command line. But you can still invoke these tests from the IDE, which is convenient when in development mode. AnimalsTest.java(the only file that follows the*Test.javanaming convention) acts as the ‘test suite’ for the entire project. By default, Karate will load all*.featurefiles from sub-directories as well. But sincesome-reusable.featureis aboveAnimalsTest.javain the folder hierarchy, it will not be picked-up. Which is exactly what we want, becausesome-reusable.featureis designed to be called only from one of the other test scripts (perhaps with some parameters being passed). You can also use tags to skip files.some-classpath-function.jsandsome-classpath-payload.jsare in the ‘root’ of the Java ‘classpath’ which means they can be easily read (and re-used) from any test-script by using theclasspath:prefix, for e.g:read('classpath:some-classpath-function.js'). Relative paths will also work.

For details on what actually goes into a script or *.feature file, refer to the

syntax guide.

Running in Eclipse or IntelliJ

If you use the open-source Eclipse Java IDE, you should consider installing the free Cucumber-Eclipse plugin. It provides syntax coloring, and the best part is that you can ‘right-click’ and run Karate test scripts without needing to write a single line of Java code.

If you use IntelliJ, Cucumber support is built-in and you can even select a single Scenario within a Feature to run at a time.

Running With JUnit

To run a script *.feature file from your Java IDE, you just need the following empty test-class in the same package. The name of the class doesn’t matter, and it will automatically run any *.feature file in the same package. This comes in useful because depending on how you organize your files and folders - you can have multiple feature files executed by a single JUnit test-class.

package animals.cats;

import com.intuit.karate.junit4.Karate;

import org.junit.runner.RunWith;

@RunWith(Karate.class)

public class CatsRunner {

}

Refer to your IDE documentation for how to run a JUnit class. Typically right-clicking on the file in the project browser or even within the editor view would bring up the “Run as JUnit Test” menu option.

Karate will traverse sub-directories and look for

*.featurefiles. For example if you have the JUnit class in thecom.mycompanypackage,*.featurefiles incom.mycompany.fooandcom.mycompany.barwill also be run. This is one reason why you may want to prefer a ‘flat’ directory structure as explained above.

Running With TestNG

You extend a class from the karate-testng Maven artifact like so. All other behavior

is the same as if using JUnit.

package animals.cats;

import com.intuit.karate.testng.KarateRunner;

public class CatsRunner extends KarateRunner {

}

Cucumber Options

You normally don’t need to - but if you want to run only a specific feature file from a JUnit test even if there are multiple *.feature files in the same folder (or sub-folders), you could use the @CucumberOptions annotation.

package animals.cats;

import com.intuit.karate.junit4.Karate;

import cucumber.api.CucumberOptions;

import org.junit.runner.RunWith;

@RunWith(Karate.class)

@CucumberOptions(features = "classpath:animals/cats/cats-post.feature")

public class CatsPostRunner {

}

The features parameter in the annotation can take an array, so if you wanted to associate

multiple feature files with a JUnit test, you could do this:

@CucumberOptions(features = {

"classpath:animals/cats/cats-post.feature",

"classpath:animals/cats/cats-get.feature"})

For TestNG: The

@CucumberOptionsannotation can be used the same way.

Command Line

Once you have a JUnit ‘runner’ class in place, it will be possible to run tests from the command-line as well. Refer to the Cucumber documentation for more, including how to enable other report output formats such as HTML. For example, if you wanted to generate a report in the Cucumber HTML format:

mvn test -Dcucumber.options="--plugin html:target/cucumber-html"

Note that the mvn test command only runs test classes that follow the *Test.java naming convention by default.

A problem you may run into is that the report is generated for every JUnit class with the @RunWith(Karate.class) annotation. So if you have multiple JUnit classes involved in a test-run, you will end up with only the report for the last class as it would have over-written everything else. There are a couple of solutions, one is to use JUnit suites - but the simplest should be to have a JUnit class (with the Karate annotation) at a level ‘above’ (in terms of folder hierarchy) all the main *.feature files in your project. So if you take the previous folder structure example:

mvn test -Dcucumber.options="--plugin junit:target/cucumber-junit.xml --tags ~@ignore" -Dtest=AnimalsTest

Here, AnimalsTest is the name of the Java class we designated to run all your tests. And yes, Cucumber has a neat way to tag your tests and the above example demonstrates how to run all tests except the ones tagged @ignore.

The reporting and tag options can be specified in the test-class via the @CucumberOptions annotation, in which case you don’t need to pass the -Dcucumber.options on the command-line:

@CucumberOptions(plugin = {"pretty", "html:target/cucumber"}, tags = {"~@ignore"})

Test Reports

You can ‘lock down’ the fact that you only want to execute the single JUnit class that functions as a test-suite - by using the following maven-surefire-plugin configuration:

<plugin>

<groupId>org.apache.maven.plugins</groupId>

<artifactId>maven-surefire-plugin</artifactId>

<version>2.10</version>

<configuration>

<includes>

<include>animals/AnimalsTest.java</include>

</includes>

<systemProperties>

<cucumber.options>--plugin junit:target/cucumber-junit.xml</cucumber.options>

</systemProperties>

</configuration>

</plugin>

Note how the cucumber.options can be specified using the <systemProperties> configuration. Options here would over-ride corresponding options specified if a @CucumberOptions annotation is present (on AnimalsTest.java). So for the above example, any plugin options present on the annotation would not take effect, but anything else (for example tags) would continue to work.

With the above in place, you don’t have to use -Dtest=AnimalsTest on the command-line any more. You may need to point your CI to the location of the JUnit XML report (e.g. target/cucumber-junit.xml) so that test-reports are generated correctly.

The Karate Demo has a working example of this set-up. Also refer to the section on switching the environment for more ways of running tests via Maven using the command-line.

The big drawback of the ‘Cucumber-native’ approach is that you cannot run tests in parallel although you have the option of choosing other ‘built-in’ report formats - for e.g. html. The recommended approach for Karate reporting in a Continuous Integration set-up is described in the next section which focuses on emitting the JUnit XML format that most CI tools can consume. The Cucumber JSON format is also emitted, which gives you plenty of options for generating pretty reports using third-party maven plugins.

And most importantly - you can run tests in parallel without having to depend on third-party hacks that introduce code-generation and config ‘bloat’ into your pom.xml.

Parallel Execution

Karate can run tests in parallel, and dramatically cut down execution time. This is a ‘core’ feature and does not depend on JUnit, TestNG or even Maven.

import com.intuit.karate.cucumber.CucumberRunner;

import com.intuit.karate.cucumber.KarateStats;

import cucumber.api.CucumberOptions;

import static org.junit.Assert.assertTrue;

import org.junit.Test;

@CucumberOptions(tags = {"~@ignore"})

public class TestParallel {

@Test

public void testParallel() {

KarateStats stats = CucumberRunner.parallel(getClass(), 5, "target/surefire-reports");

assertTrue("scenarios failed", stats.getFailCount() == 0);

}

}

Things to note:

- You don’t use a JUnit runner, and you write a plain vanilla JUnit test (it could very well be TestNG or plain old Java) using the

CucumberRunner.parallel()static method inkarate-core. - You can use the returned

KarateStatsto check if any scenarios failed. - The first argument can be any class that marks the ‘root package’ in which

*.featurefiles will be looked for, and sub-directories will be also scanned. As shown above you would typically refer to the enclosing test-class itself. - The second argument is the number of threads to use.

- JUnit XML reports will be generated in the path you specify as the third parameter, and you can easily configure your CI to look for these files after a build (for e.g. in

**/*.xmlor**/surefire-reports/*.xml). This argument is optional and will default totarget/surefire-reports. - Cucumber JSON reports will be generated side-by-side with the JUnit XML reports and with the same name, except that the extension will be

.jsoninstead of.xml. - No other reports will be generated. If you specify a

pluginoption via the@CucumberOptionsannotation, or the command-line, or the ‘maven-surefire-plugin’<systemProperties>- it will be ignored. - But all other options passed to

@CucumberOptionswould work as expected, provided you point theCucumberRunnerto the annotated class as the first argument. Note that in this example, any*.featurefile tagged as@ignorewill be skipped. - For convenience, some stats are logged to the console when execution completes, which should look something like this:

======================================================

elapsed time: 1.778000 | test time: 7.895000

thread count: 5 | parallel efficiency: 0.888076

scenarios: 12 | failed: 0 | skipped: 0

======================================================

This is the preferred way of automating the execution of all Karate tests in a project, mainly because the other ‘native’ Cucumber reports (e.g. HTML) are not thread-safe. In other words, please rely on the CucumberRunner.parallel() JUnit XML and Cucumber JSON output for CI and test result reporting, and if you see any problems, or if your CI tool does not support the JUnit XML format, please submit a defect report.

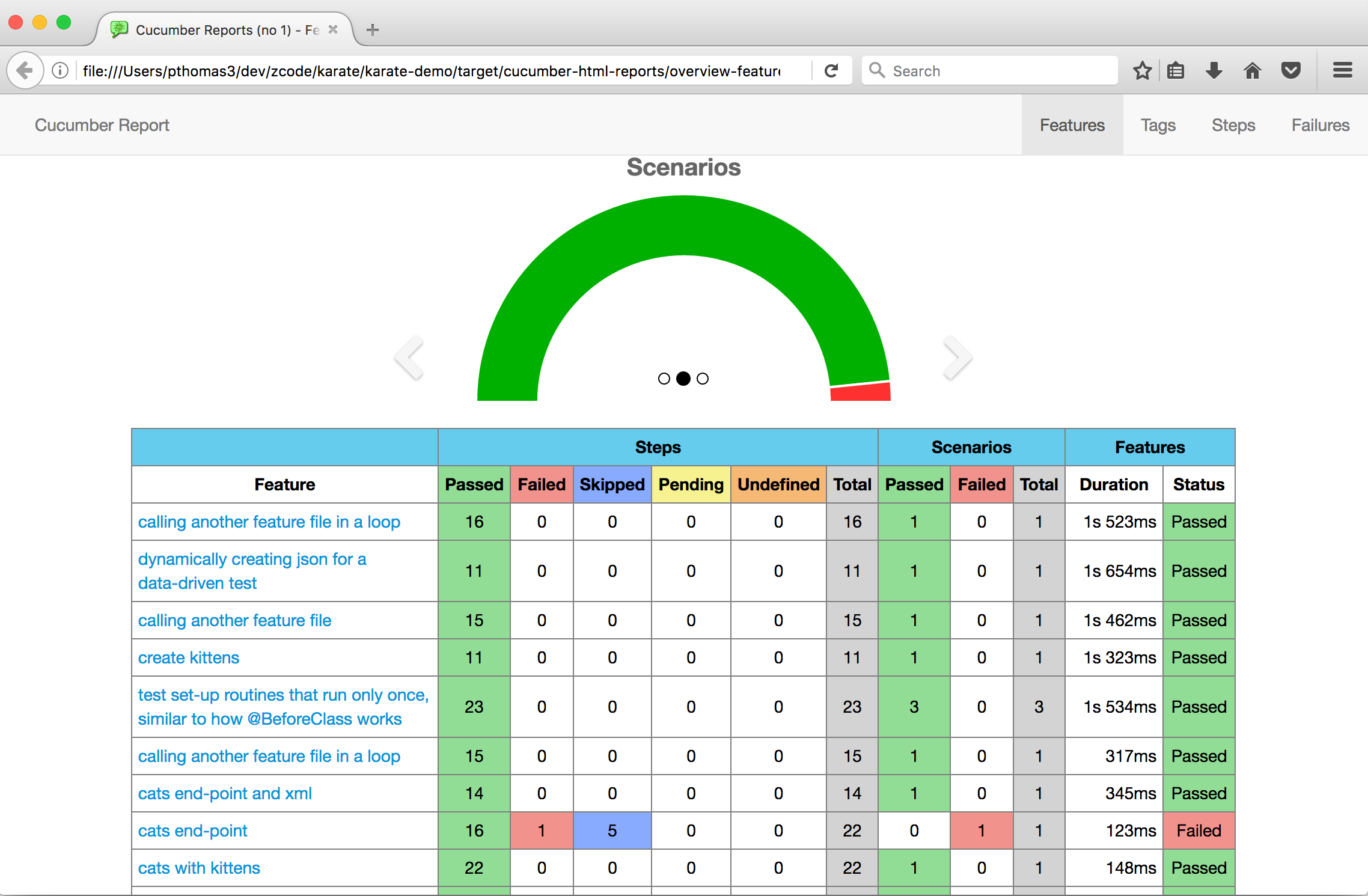

The Karate Demo has a working example of this set-up. It also explains how a third-party library can be easily used to generate some very nice-looking reports. For example, here below is an actual report generated by the cucumber-reporting open-source library.

The demo also features code-coverage using Jacoco.

Logging

This is optional, and Karate will work without the logging config in place, but the default console logging may be too verbose for your needs.

Karate uses LOGBack which looks for a file called logback-test.xml

on the classpath. If you use the Maven <test-resources> tweak described earlier (recommended),

keep this file in src/test/java, or else it should go into src/test/resources.

Here is a sample logback-test.xml for you to get started.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<configuration>

<appender name="STDOUT" class="ch.qos.logback.core.ConsoleAppender">

<encoder>

<pattern>%d{HH:mm:ss.SSS} [%thread] %-5level %logger{36} - %msg%n</pattern>

</encoder>

</appender>

<appender name="FILE" class="ch.qos.logback.core.FileAppender">

<file>target/karate.log</file>

<encoder>

<pattern>%d{HH:mm:ss.SSS} [%thread] %-5level %logger{36} - %msg%n</pattern>

</encoder>

</appender>

<logger name="com.intuit" level="DEBUG"/>

<root level="info">

<appender-ref ref="STDOUT" />

<appender-ref ref="FILE" />

</root>

</configuration>

You can change the com.intuit logger level to INFO to reduce the amount of logging. When the level is DEBUG the entire request and response payloads are logged.

Configuration

You can skip this section and jump straight to the Syntax Guide if you are in a hurry to get started with Karate. Things will work even if the

karate-config.jsfile is not present.

The only ‘rule’ is that on start-up Karate expects a file called karate-config.js to exist on the classpath and contain a JavaScript function. Karate will invoke this function and from that point onwards, you are free to set config properties in a variety of ways. One possible method is shown below, based on reading a Java system property.

function() {

var env = karate.env; // get java system property 'karate.env'

karate.log('karate.env system property was:', env);

if (!env) {

env = 'dev'; // a custom 'intelligent' default

}

var config = { // base config

env: env,

appId: 'my.app.id',

appSecret: 'my.secret',

someUrlBase: 'https://some-host.com/v1/auth/',

anotherUrlBase: 'https://another-host.com/v1/'

};

if (env == 'stage') {

// over-ride only those that need to be

config.someUrlBase = 'https://stage-host/v1/auth';

} else if (env == 'e2e') {

config.someUrlBase = 'https://e2e-host/v1/auth';

}

// don't waste time waiting for a connection or if servers don't respond within 5 seconds

karate.configure('connectTimeout', 5000);

karate.configure('readTimeout', 5000);

return config;

}

The function is expected to return a JSON object and all keys and values in that JSON object will be made available as script variables. And that’s all there is to Karate configuration.

The

karateobject has a few helper methods described in detail later in this document where thecallkeyword is explained. Here above, you seekarate.log(),karate.envandkarate.configure()being used.

This decision to use JavaScript for config is influenced by years of experience with the set-up of complicated test-suites and fighting with Maven profiles, Maven resource-filtering and the XML-soup that somehow gets summoned by the Maven AntRun plugin.

Karate’s approach frees you from Maven, is far more expressive, allows you to eyeball all environments in one place, and is still a plain-text file. If you want, you could even create nested chunks of JSON that ‘name-space’ your config variables.

This approach is indeed slightly more complicated than traditional *.properties files - but you need this complexity. Keep in mind that these are tests (not production code) and this config is going to be maintained more by the dev or QE team instead of the ‘ops’ or operations team.

And there is no more worrying about Maven profiles and whether the ‘right’ *.properties file has been copied to the proper place.

Switching the Environment

There is only one thing you need to do to switch the environment - which is to set a Java system property.

The recipe for doing this when running Maven from the command line is:

mvn test -DargLine="-Dkarate.env=e2e"

You can refer to the documentation of the

Maven Surefire Plugin

for alternate ways of achieving this, but the argLine approach is the simplest and should be more than sufficient for your Continuous Integration or test-automation needs.

Here’s a reminder that running any single JUnit test via Maven can be done by:

mvn test -Dtest=CatsRunner

Where CatsRunner is the JUnit class name (in any package) you wish to run.

Karate is flexible, you can easily over-write config variables within each individual test-script - which is very convenient when in dev-mode or rapid-prototyping.

Just for illustrative purposes, you could ‘hard-code’ the karate.env for a specific JUnit test like this. Since CI test-automation would typically use a designated ‘top-level suite’ test-runner, you can actually have these individual test-runners lying around without any ill-effects. They are obviously useful for dev-mode troubleshooting. To ensure that they don’t get run by CI by mistake - just don’t use the *Test.java naming convention.

package animals.cats;

import com.intuit.karate.junit4.Karate;

import org.junit.BeforeClass;

import org.junit.runner.RunWith;

@RunWith(Karate.class)

public class CatsRunner {

@BeforeClass

public static void before() {

System.setProperty("karate.env", "pre-prod");

}

}

Syntax Guide

Script Structure

Karate scripts are technically in ‘Gherkin’ format - but all you need to grok as someone who needs to test web-services are the three sections: Feature, Background and Scenario. There can be multiple Scenario-s in a *.feature file.

Lines that start with a # are comments.

Feature: brief description of what is being tested

more lines of description if needed.

Background:

# steps here are expecuted before each Scenario in this file

Scenario: brief description of this scenario

# steps for this scenario

Scenario: a different scenario

# steps for this other scenario

Given-When-Then

The business of web-services testing requires access to low-level aspects such as HTTP headers, URL-paths, query-parameters, complex JSON or XML payloads and response-codes. And Karate gives you control over these aspects with the small set of keywords focused on HTTP such as url, path, param, etc.

Karate does not attempt to have tests be in “natural language” like how Cucumber tests are traditionally expected to be. That said, the syntax is very concise, and the convention of every step having to start with either Given, And, When or Then, makes things very readable. You end up with a decent approximation of BDD even though web-services by nature are “headless”, without a UI, and not really human-friendly.

Cucumber vs Karate

If you are familiar with Cucumber (JVM), you may be wondering if you need to write step-definitions. The answer is no.

Karate’s approach is that all the step-definitions you need in order to work with HTTP, JSON and XML have been already implemented. And since you can easily extend Karate using JavaScript, there is no need to compile Java code any more.

The following table summmarizes some key differences between Cucumber and Karate.

| :white_small_square: | Cucumber | Karate |

|---|---|---|

| Step Definitions Built-In | No. You need to keep implementing them as your functionality grows. This can get very tedious. | :white_check_mark: Yes. No extra Java code needed. |

| Single Layer of Code To Maintain | No. There are 2 Layers. The Gherkin spec or *.feature files make up one layer, and you will also have the corresponding Java step-definitions. |

:white_check_mark: Yes. Only 1 layer of Karate-script (based on Gherkin). |

| Readable Specification | Yes. Cucumber will read like natural language if you implement the step-definitions right. | :x: No. Although Karate is simple, and a true DSL, it is ultimately a mini-programming language. But it is perfect for testing web-services at the level of HTTP requests and responses. |

| Re-Use Feature Files | No. Cucumber does not support being able to call (and thus re-use) other *.feature files from a test-script. |

:white_check_mark: Yes. |

| Dynamic Data-Driven Testing | No. Cucumber’s Scenario Outline expects the Examples to contain a fixed set of rows. |

:white_check_mark: Yes. Karate’s support for calling other *.feature files allows you to use a JSON array as the data-source. |

| Parallel Execution | No. There are some challenges (especially with reporting) and you can find various discussions and third-party projects on the web that attempt to close this gap: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | :white_check_mark: Yes. |

| Run ‘Set-Up’ Routines Only Once | No. Cucumber has a limitation where Background steps are re-run for every Scenario and worse - even for every Examples row within a Scenario Outline. This has been a highly-requested open issue for a long time. |

:white_check_mark: Yes. |

One nice thing about the design of the underlying Cucumber framework is that script-steps are treated the same no matter whether they start with the keyword Given, And, When or Then. What this means is that you are free to use whatever makes sense for you. You could even have all the steps start with When and Karate won’t care.

In fact Cucumber supports the catch-all symbol ‘*’ - instead of forcing you to use Given, When or Then. This is perfect for those cases where it really doesn’t make sense - for example the Background section or when you use the def or set syntax. When eyeballing a test-script, think of the * as a ‘bullet-point’.

You can read more about the Given-When-Then convention at the Cucumber reference documentation.

Since Karate is based on Cucumber, you can also employ data-driven techniques such as expressing data-tables in test scripts.

Another good thing that Karate inherits is the nice IDE support for Cucumber that IntelliJ and Eclipse have. So you can do things like right-click and run a *.feature file (or scenario) without needing to use a JUnit runner.

For a detailed discussion on BDD and how Karate relates to Cucumber, please refer to this blog-post: Yes, Karate is not true BDD.

With the formalities out of the way, let’s dive straight into the syntax.

Setting and Using Variables

def

Set a named variable

# assigning a string value:

Given def myVar = 'world'

# using a variable

Then print myVar

# assigning a number (you can use '*' instead of Given / When / Then)

* def myNum = 5

Note that def will over-write any variable that was using the same name earlier. Keep in mind that the start-up configuration routine could have already initialized some variables before the script even started.

The examples above are simple, but a variety of expression ‘shapes’ are supported on the right hand side of the = symbol. The section on Karate Expressions goes into the details.

assert

Assert if an expression evaluates to true

Once defined, you can refer to a variable by name. Expressions are evaluated using the embedded JavaScript engine. The assert keyword can be used to assert that an expression returns a boolean value.

Given def color = 'red '

And def num = 5

Then assert color + num == 'red 5'

Everything to the right of the assert keyword will be evaluated as a single expression.

Something worth mentioning here is that you would hardly need to use assert in your test scripts. Instead you would typically use the match keyword, that is designed for performing powerful assertions against JSON and XML response payloads.

print

Log to the console

You can use print to log variables to the console in the middle of a script. All of the text to the right of the print keyword will be evaluated as a single expression (somewhat like assert).

* print 'the value of a is ' + a

When dealing with complex JSON, you would often want to ‘pretty print’ data which is nicely indented. The built-in karate object is explained in detail later, but for now, note that this is also injected into print (and even assert) statements, and it has a helpful pretty method, that takes a JSON argument.

* def myJson = { foo: 'bar', baz: [1, 2, 3] }

* print 'pretty print:\n' + karate.pretty(myJson)

Which results in the following output:

20:29:11.290 [main] INFO com.intuit.karate - [print] pretty print:

{

"foo": "bar",

"baz": [

1,

2,

3

]

}

It is possible to pretty print XML in a similar way using the karate object. Also refer to the configure keyword on how to switch on pretty-printing of all HTTP requests and responses.

‘Native’ data types

Native data types mean that you can insert them into a script without having to worry about enclosing them in strings and then having to ‘escape’ double-quotes all over the place. They seamlessly fit ‘in-line’ within your test script.

JSON

Note that the parser is ‘lenient’ so that you don’t have to enclose all keys in double-quotes.

* def cat = { name: 'Billie', scores: [2, 5] }

* assert cat.scores[1] == 5

When asserting for expected values in JSON or XML you are probably better off using match instead of assert.

* def cats = [{ name: 'Billie' }, { name: 'Bob' }]

* match cats[1] == { name: 'Bob' }

Karate’s native support for JSON means that you can assign parts of a JSON instance into another variable, which is useful when dealing with complex response payloads.

* def first = cats[0]

* match first == { name: 'Billie' }

For manipulating or updating JSON (or XML) using path expressions, refer to the set keyword.

XML

Given def cat = <cat><name>Billie</name><scores><score>2</score><score>5</score></scores></cat>

# sadly, xpath list indexes start from 1

Then match cat/cat/scores/score[2] == '5'

# but karate allows you to traverse xml like json !!

Then match cat.cat.scores.score[1] == 5

Embedded Expressions

Karate has a very useful JSON ‘templating’ approach. Variables can be referred to within JSON, for example:

When def user = { name: 'john', age: 21 }

And def lang = 'en'

Then def session = { name: '#(user.name)', locale: '#(lang)', sessionUser: '#(user)' }

So the rule is - if a string value within a JSON (or XML) object declaration is enclosed between #( and ) - it will be evaluated as a JavaScript expression. And any variables which are alive in the context can be used in this expression.

This comes in useful in some cases - and avoids needing to use the set keyword or JavaScript functions to manipulate JSON. So you get the best of both worlds: the elegance of JSON to express complex nested data - while at the same time being able to dynamically plug values (that could even be other JSON object-trees) into a JSON ‘template’.

A special case of embedded expressions can remove a JSON key (or XML element / attribute) if the expression evaluates to null.

Multi-Line Expressions

The keywords def, set, match and request take multi-line input as the last argument. This is useful when you want to express a one-off lengthy snippet of text in-line, without having to split it out into a separate file. Here are some examples:

# instead of:

* def cat = <cat><name>Billie</name><scores><score>2</score><score>5</score></scores></cat>

# this is more readable:

* def cat =

"""

<cat>

<name>Billie</name>

<scores>

<score>2</score>

<score>5</score>

</scores>

</cat>

"""

# example of a request payload in-line

Given request

"""

<?xml version='1.0' encoding='UTF-8'?>

<S:Envelope xmlns:S="http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/soap/envelope/">

<S:Body>

<ns2:QueryUsageBalance xmlns:ns2="http://www.mycompany.com/usage/V1">

<ns2:UsageBalance>

<ns2:LicenseId>12341234</ns2:LicenseId>

</ns2:UsageBalance>

</ns2:QueryUsageBalance>

</S:Body>

</S:Envelope>

"""

# example of a payload assertion in-line

Then match response ==

"""

{ id: { domain: "DOM", type: "entityId", value: "#ignore" },

created: { on: "#ignore" },

lastUpdated: { on: "#ignore" },

entityState: "ACTIVE"

}

"""

table

A simple way to create JSON

Now that we have seen how JSON is a ‘native’ data type that Karate understands, there is a very nice way to create JSON using Cucumber’s support for expressing data-tables.

* table cats =

| name | age |

| 'Bob' | 2 |

| 'Wild' | 4 |

| 'Nyan' | 3 |

* match cats == [{name: 'Bob', age: 2}, {name: 'Wild', age: 4}, {name: 'Nyan', age: 3}]

The match keyword is explained later, but it should be clear right away how convenient the table keyword is. JSON can be combined with the ability to call other *.feature files to achieve dynamic data-driven testing in Karate.

Notice that in the above example, string values within the table need to be enclosed in quotes. Otherwise they would be evaluated as expressions - which does come in useful for some dynamic data-driven situations:

* def one = 'hello'

* def two = { baz: 'world' }

* table json =

| foo | bar |

| one | 1 |

| two.baz | 2 |

* match json == [{ foo: 'hello', bar: 1 }, { foo: 'world', bar: 2 }]

text

Don’t parse, treat as raw text

Not something you would commonly use, but in some cases you need to disable Karate’s default behavior of attempting to parse anything that looks like JSON (or XML) when using multi-line expressions. This is especially relevant when manipulating GraphQL queries - because although they look suspiciously like JSON, they are not, and tend to confuse Karate’s internals. The other advantage is that ‘white space’ such as ‘line-feeds’ (which are significant in GraphQL) would be handled correctly, and retained. And as shown in the example below, having text ‘in-line’ is useful especially when you use the Scenario Outline: and Examples: for data-driven tests.

Scenario Outline:

# note the 'text' keyword instead of 'def'

* text query =

"""

mutation {

someEntity(input: {

clientMutationId: "1"

someChild: {

name: "<name>"

}

}) {

clientMutationId

someChild {

id

name

}

}

}

"""

Given path 'graphql'

And request { query: '#(query)' }

And header Accept = 'application/json'

When method post

Then status 200

And def child = response.data.someEntity.someChild

And match child == { id: '#notnull', name: '<name>' }

Examples:

| name |

| John |

| Smith |

Note that if you did not need to inject Examples: into ‘placeholders’ enclosed within < and >, reading from a file with the extension *.txt may have been sufficient.

replace

Text Placeholder Replacement

Important: this is applicable only to text content. For JSON and XML - which are natively supported by Karate, please refer to how to use the

setkeyword.

Karate provides an elegant ‘native-like’ experience for placeholder substitution within strings or text content. This is useful in any situation where you need to concatenate dynamic string fragments to form content such as GraphQL or SQL.

The placeholder format defaults to angle-brackets, for example: <replaceMe>. Here is how to replace one placeholder at a time:

* def text = 'hello <foo> world'

* replace text.foo = 'bar'

* match text == 'hello bar world'

Karate makes it really easy to substitute multiple placeholders in a single, readable step as follows:

* def text = 'hello <one> world <two> bye'

* replace text

| token | value |

| one | 'cruel' |

| two | 'good' |

* match text == 'hello cruel world good bye'

Note how strings have to be enclosed in quotes. This is so that you can mix expressions into text replacements as shown below. This example also shows how you can use a custom placeholder format instead of the default:

* def text = 'hello <one> world ${two} bye'

* def first = 'cruel'

* def json = { second: 'good' }

* replace text

| token | value |

| one | first |

| ${two} | json.second |

* match text == 'hello cruel world good bye'

Refer to this file for a detailed example: replace.feature

yaml

Import YAML as JSON

For those who may prefer YAML as a simpler way to represent data, Karate allows you to read YAML content ‘in-line’ or even from a file - and it will be auto-converted to JSON.

# reading yaml 'in-line', note the 'yaml' keyword instead of 'def'

* yaml foo =

"""

name: John

input:

id: 1

subType:

name: Smith

deleted: false

"""

# the data is now JSON, so you can do JSON-things with it

* match foo ==

"""

{

name: 'John',

input: {

id: 1,

subType: { name: 'Smith', deleted: false }

}

}

"""

# yaml from a file (the extension matters), and the data-type of 'bar' would be JSON

* def bar = read('data.yaml')

JavaScript Functions

JavaScript Functions are also ‘native’. And yes, functions can take arguments.

Standard JavaScript syntax rules apply.

ES6 arrow functions are not supported.

* def greeter = function(name){ return 'hello ' + name }

* assert greeter('Bob') == 'hello Bob'

Java Interop

For more complex functions you are better off using the multi-line ‘doc-string’ approach. This example actually calls into existing Java code, and being able to do this opens up a whole lot of possibilities. The JavaScript interpreter will try to convert types across Java and JavaScript as smartly as possible. For e.g. JSON objects become Java Map-s, JSON arrays become Java List-s, and Java Bean properties are accessible (and update-able) using dot notation e.g. ‘object.name’

* def dateStringToLong =

"""

function(s) {

var SimpleDateFormat = Java.type('java.text.SimpleDateFormat');

var sdf = new SimpleDateFormat("yyyy-MM-dd'T'HH:mm:ss.SSSZ");

return sdf.parse(s).time; // '.getTime()' would also have worked instead of '.time'

}

"""

* assert dateStringToLong("2016-12-24T03:39:21.081+0000") == 1482550761081

More examples of Java interop and how to invoke custom code can be found in the section on Calling Java.

The call keyword provides an alternate way of calling JavaScript functions that have only one argument. The argument can be provided after the function name, without parentheses, which makes things slightly more readable (and less cluttered) especially when the solitary argument is JSON.

* def timeLong = call dateStringToLong '2016-12-24T03:39:21.081+0000'

* assert timeLong == 1482550761081

# a better example, with a JSON argument

* def greeter = function(name){ return 'Hello ' + name.first + ' ' + name.last + '!' }

* def greeting = call greeter { first: 'John', last: 'Smith' }

Reading Files

Karate makes re-use of payload data, utility-functions and even other test-scripts as easy as possible. Teams typically define complicated JSON (or XML) payloads in a file and then re-use this in multiple scripts. Keywords such as set and remove allow you to to ‘tweak’ payload-data to fit the scenario under test. You can imagine how this greatly simplifies setting up tests for boundary conditions. And such re-use makes it easier to re-factor tests when needed, which is great for maintainability,

Reading files is achieved using the read keyword. By default, the file is expected to be in the same folder (package) as the *.feature file. But you can prefix the name with classpath: in which case the ‘root’ folder would be src/test/java (assuming you are using the recommended folder structure).

Prefer classpath: when a file is expected to be heavily re-used all across your project. And yes, relative paths will work.

# json

* def someJson = read('some-json.json')

* def moreJson = read('classpath:more-json.json')

# xml

* def someXml = read('../common/my-xml.xml')

# import yaml (will be converted to json)

* def jsonFromYaml = read('some-data.yaml')

# string

* def someString = read('classpath:messages.txt')

# javascript (will be evaluated)

* def someValue = read('some-js-code.js')

# if the js file evaluates to a function, it can be re-used later using the 'call' keyword

* def someFunction = read('classpath:some-reusable-code.js')

* def someCallResult = call someFunction

# the following short-cut is also allowed

* def someCallResult = call read('some-js-code.js')

You can also re-use other *.feature files from test-scripts:

# perfect for all those common authentication or 'set up' flows

* def result = call read('classpath:some-reusable-steps.feature')

If a file does not end in .json, .xml, .yaml, .js or .txt - it is treated as a stream which is typically what you would need for multipart file uploads.

* def someStream = read('some-pdf.pdf')

Since it is internally implemented as a JavaScript function, you can mix calls to read() freely wherever JavaScript expressions are allowed:

* def someBigString = read('first.txt') + read('second.txt')

And a very common need would be to use a file as the request body.

Given request read('some-big-payload.json')

Take a look at the Karate Demos for real-life examples of how you can use files for matching HTTP responses.

Type Conversion

Internally, Karate will auto-convert JSON (and even XML) to Java Map objects. And JSON arrays would become Java List-s. But you will never need to worry about this internal data-representation most of the time.

In some rare cases, for e.g. if you acquired a string from some external source, or if you generated JSON (or XML) by concatenating text, you may want to convert a string to JSON and vice-versa. You can even perform a conversion from XML to JSON if you want.

One example of when you may want to convert JSON (or XML) to a string is when you are passing a payload to custom code via Java interop. Do note that when passing JSON, the default Map and List representations should suffice for most needs (see example), and using them would avoid un-necessary string-conversion.

So you have the following type markers you can use instead of def:

string- convert JSON or any other data-type (except XML) to a stringjson- convert XML, a map-like or list-like object, a string, or even a Java bean (POJO) into JSONxml- convert JSON, a map-like object, a string, or even a Java bean (POJO) into XMLxmlstring- specifically for converting XML into a string

These are best explained in this example file: type-conv.feature

If you want to ‘pretty print’ a JSON or XML value with indenting, refer to the documentation of the print keyword.

Karate Expressions

Before we get to the HTTP keywords, it is worth doing a recap of the various ‘shapes’ that the right-hand-side of an assignment statement can take:

| Example | Shape | Description |

|---|---|---|

* def foo = 'bar' |

primitive | simple strings, numbers or booleans |

* def foo = 'bar' + baz[0] |

JS | any valid JavaScript expression, and variables can be mixed in |

* def foo = (bar.baz + 1) |

JS | Karate assumes that users need JsonPath most of the time, so in some rare cases - you may need to force Karate to evaluate the Right-Hand-Side as JavaScript, which is easily achieved by wrapping the RHS in parantheses |

* def foo = { bar: 1 } |

JSON | anything that starts with a { or a [ is treated as JSON, use text instead of def if you need to suppress the default behavior |

* def foo = <foo>bar</foo> |

XML | anything that starts with a < is treated as XML, use text instead of def if you need to suppress the default behavior |

* def foo = function(arg){ return arg + bar } |

JS Function | anything that starts with function(...){ is treated as a JS function. |

* def foo = read('bar.json') |

Read | using the built-in read() function |

* def foo = $.bar[0] |

JsonPath | short-cut JsonPath on the response |

* def foo = /bar/baz |

XPath | short-cut XPath on the response |

* def foo = bar.baz[0] |

Named JsonPath | JsonPath on the variable bar |

* def foo = bar/baz/ban[1] |

Named XPath | XPath on the variable bar |

* def foo = get bar $..baz[?(@.ban)] |

get JsonPath |

JsonPath on the variable bar, use get in cases where Karate fails to detect JsonPath correctly on the RHS (especially when using filter-criteria) |

* def foo = get bar count(/baz//ban) |

get XPath |

XPath on the variable bar, use get in cases where Karate fails to detect XPath correctly on the RHS (especially when using XPath functions) |

* def foo = karate.pretty(bar) |

karate JS |

using the built-in karate object in JS expressions |

* def Foo = Java.type('com.mycompany.Foo') |

Java Type | Java Interop, and even package-name-spaced one-liners like java.lang.System.currentTimeMillis() are possible |

* def foo = call bar { baz: 'ban' } |

call |

or callonce, where expressions like read('foo.js') are allowed as the object to be called or the argument |

Core Keywords

They are url, path, request, method and status.

These are essential HTTP operations, they focus on setting one (non-keyed) value at a time and don’t involve any ‘=’ signs in the syntax.

url

Given url 'https://myhost.com/v1/cats'

A URL remains constant until you use the url keyword again, so this is a good place to set-up the ‘non-changing’ parts of your REST URL-s.

A URL can take expressions, so the approach below is legal. And yes, variables can come from global config.

Given url 'https://' + e2eHostName + '/v1/api'

path

REST-style path parameters. Can be expressions that will be evaluated. Comma delimited values are supported which can be more convenient, and takes care of URL-encoding and appending ‘/’ where needed.

Given path 'documents/' + documentId + '/download'

# this is equivalent to the above

Given path 'documents', documentId, 'download'

# or you can do the same on multiple lines if you wish

Given path 'documents'

And path documentId

And path 'download'

Note that the path ‘resets’ after any HTTP request is made but not the url. The Hello World is a great example of ‘REST-ful’ use of the url when the test focuses on a single REST ‘resource’. Look at how the path did not need to be specified for the second HTTP get call since /cats is part of the url.

request

In-line JSON:

Given request { name: 'Billie', type: 'LOL' }

In-line XML:

And request <cat><name>Billie</name><type>Ceiling</type></cat>

From a file in the same package. Use the classpath: prefix to load from the

classpath instead.

Given request read('my-json.json')

You could always use a variable:

And request myVariable

In most cases you won’t need to set the Content-Type header as Karate will automatically do the right thing depending on the data-type of the request.

Defining the request is mandatory if you are using an HTTP method that expects a body such as post. If you really need to have an empty body, you can use an empty string as shown below, and you can force the right Content-Type header by using the header keyword.

Given request ''

And header Content-Type = 'text/html'

method

The HTTP verb - get, post, put, delete, patch, options, head, connect, trace.

Lower-case is fine.

When method post

It is worth internalizing that during test-execution, it is upon the method keyword that the actual HTTP request is issued. Which suggests that the step should be in the When

form, for e.g.: When method post. And steps that follow should logically be in the Then form.

For example:

When method get

# the step that immediately follows the above would typically be:

Then status 200

status

This is a shortcut to assert the HTTP response code.

Then status 200

And this assertion will cause the test to fail if the HTTP response code is something else.

See also responseStatus.

Keywords that set key-value pairs

They are param, header, cookie, form field and multipart field.

The syntax will include a ‘=’ sign between the key and the value. The key should not be within quotes.

To make dynamic data-driven testing easier, the following keywords also exist:

params,headers,cookiesandform fields. They use JSON to build the relevant parts of the HTTP request.

param

Setting query-string parameters:

Given param someKey = 'hello'

And param anotherKey = someVariable

# multi-value params are also supported

* param myParam = 'foo', 'bar'

You can also use JSON to set multiple query-parameters in one-line using params and this is especially useful for dynamic data-driven testing.

header

You can use functions or expressions:

Given header Authorization = myAuthFunction()

And header transaction-id = 'test-' + myIdString

It is worth repeating that in most cases you won’t need to set the Content-Type header as Karate will automatically do the right thing depending on the data-type of the request.

Because of how easy it is to set HTTP headers, Karate does not provide any special keywords for things like

the Accept header. You simply do

something like this:

Given path 'some/path'

And request { some: 'data' }

And header Accept = 'application/json'

When method post

Then status 200

A common need is to send the same header(s) for every request, and configure headers (with JSON) is how you can set this up once for all subsequent requests. And if you do this within a Background: section, it would apply to all Scenario: sections within the *.feature file.

* configure headers = { 'Content-Type': 'application/xml' }

Note: in this example above,

Content-Typehad to be enclosed in quotes because the hyphen-is not a legal JSON key-name.

If you need headers to be dynamically generated for each HTTP request, use a JavaScript function with configure headers instead of JSON.

Multi-value headers (though rarely used in the wild) are also supported:

* header myHeader = 'foo', 'bar'

Also look at the headers keyword which uses JSON and makes some kinds of dynamic data-driven testing easier.

cookie

Setting a cookie:

Given cookie foo = 'bar'

You also have the option of setting multiple cookies in one-step using the cookies keyword.

Note that any cookies returned in the HTTP response would be automatically set for any future requests. This mechanism works by calling configure cookies behind the scenes and if you need to stop auto-adding cookies for future requests, just do this:

* configure cookies = null

Also refer to the built-in variable responseCookies for how you can access and perform assertions on cookie data values.

form field

HTML form fields would be URL-encoded when the HTTP request is submitted (by the method step). You would typically use these to simulate a user sign-in and then grab a security token from the response. For example:

Given path 'login'

And form field username = 'john'

And form field password = 'secret'

When method post

Then status 200

And def authToken = response.token

Multi-values are supported the way you would expect (e.g. for simulating check-boxes and multi-selects):

* form field selected = 'apple', 'orange'

You can also dynamically set multiple fields in one step using the form fields keyword.

multipart field

Use this for building multipart named (form) field requests. This is typically combined with multipart file as shown below.

multipart file

Given multipart file myFile = { read: 'test.pdf', filename: 'upload-name.pdf', contentType: 'application/pdf' }

And multipart field message = 'hello world'

When method post

Then status 200

Note that multipart file takes a JSON argument so that you can easily set the filename and the contentType (mime-type) in one step.

read: mandatory, - the name of a file, and theclasspath:prefix also is allowed.filename: optional, will default to the multipart field name if not specifiedcontentType: optional, will default toapplication/octet-stream

When ‘multipart’ content is involved, the Content-Type header of the HTTP request defaults to multipart/form-data.

You can over-ride it by using the header keyword before the method step. Look at

multipart entity for an example.

multipart entity

This is technically not in the key-value form:

multipart field name = 'foo', but logically belongs here in the documentation.

Use this for multipart content items that don’t have field-names. Here below is an example that

also demonstrates using the multipart/related content-type.

Given path '/v2/documents'

And multipart entity read('foo.json')

And multipart field image = read('bar.jpg')

And header Content-Type = 'multipart/related'

When method post

Then status 201

Keywords that set multiple key-value pairs in one step

params, headers, cookies and form fields take a single JSON argument (which can be in-line or a variable reference), and this enables certain types of dynamic data-driven testing. Here is a good example in the demos: dynamic-params.feature

params

* params { searchBy: 'client', active: true, someList: [1, 2, 3] }

See also param.

headers

* def someData = { Authorization: 'sometoken', tx_id: '1234', extraTokens: ['abc', 'def'] }

* headers someData

See also header.

cookies

* cookies { someKey: 'someValue', foo: 'bar' }

See also cookie.

form fields

* def credentials = { username: '#(user.name)', password: 'secret', projects: ['one', 'two'] }

* form fields credentials

See also form field.

SOAP

Since a SOAP request needs special handling, this is the only case where the

method step is not used to actually fire the request to the server.

soap action

The name of the SOAP action specified is used as the ‘SOAPAction’ header. Here is an example which also demonstrates how you could assert for expected values in the response XML.

Given request read('soap-request.xml')

When soap action 'QueryUsageBalance'

Then status 200

And match response /Envelope/Body/QueryUsageBalanceResponse/Result/Error/Code == 'DAT_USAGE_1003'

And match response /Envelope/Body/QueryUsageBalanceResponse == read('expected-response.xml')

Here is a working example of calling a SOAP service from the Karate project test-suite: soap.feature

There’s also a few examples that show various ways of parameter-izing and dynamically manipulating SOAP requests. Karate is quite flexible, and allows you to choose options and evolve a pattern for tests - that fits your environment: xml.feature

Managing Headers, SSL, Timeouts and HTTP Proxy

configure

You can adjust configuration settings for the HTTP client used by Karate using this keyword. The syntax is similar to def but instead of a named variable, you update configuration. Here are the configuration keys supported:

| Key | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

headers |

JavaScript Function | See configure headers |

headers |

JSON | See configure headers |

cookies |

JSON | Just like configure headers, but for cookies. You will typically never use this, as response cookies are auto-added to all future requests. However, if you need to clear any cookies, just do configure cookies = null at any time. |

logPrettyRequest |

boolean | Pretty print the request payload JSON or XML with indenting (default false) |

logPrettyResponse |

boolean | Pretty print the response payload JSON or XML with indenting (default false) |

printEnabled |

boolean | Can be used to suppress the print output when not in ‘dev mode’ (default true) |

ssl |

boolean | Enable HTTPS calls without needing to configure a trusted certificate or key-store. |

ssl |

string | Like above, but force the SSL algorithm to one of these values. (The above form internally defaults to TLS if simply set to true). |

connectTimeout |

integer | Set the connect timeout (milliseconds). The default is 30000 (30 seconds). |

readTimeout |

integer | Set the read timeout (milliseconds). The default is 30000 (30 seconds). |

proxy |

string | Set the URI of the HTTP proxy to use. |

proxy |

JSON | For a proxy that requires authentication, set the uri, username and password. (See example below). |

httpClientClass |

string | See karate-mock-servlet |

httpClientInstance |

Java Object | See karate-mock-servlet |

userDefined |

JSON | See karate-mock-servlet |

Examples:

# pretty print the response payload

* configure logPrettyResponse = true

# enable ssl (and no certificate is required)

* configure ssl = true

# enable ssl and force the algorithm to TLSv1.2

* configure ssl = 'TLSv1.2'

# time-out if the response is not received within 10 seconds (after the connection is established)

* configure readTimeout = 10000

# set the uri of the http proxy server to use

* configure proxy = 'http://my.proxy.host:8080'

# proxy which needs authentication

* configure proxy = { uri: 'http://my.proxy.host:8080', username: 'john', password: 'secret' }

And if you need to set some of these ‘globally’ you can easily do so using the karate object in karate-config.js.

Preparing, Manipulating and Matching Data

Now it should be clear how Karate makes it easy to express JSON or XML. If you read from a file, the advantage is that multiple scripts can re-use the same data.

Once you have a JSON or XML object, Karate provides multiple ways to manipulate, extract or transform data. And you can easily assert that the data is as expected by comparing it with another JSON or XML object.

match

Payload Assertions / Smart Comparison

The match operation is smart because white-space does not matter, and the order of keys (or data elements) does not matter. Karate is even able to ignore fields you choose - which is very useful when you want to handle server-side dynamically generated fields such as UUID-s, time-stamps, security-tokens and the like.

The match syntax involves a double-equals sign ‘==’ to represent a comparison (and not an assignment ‘=’).

Since match and set go well together, they are both introduced in the examples in the section below.

set

Manipulating Data

Game, set and match - Karate !

Setting values on JSON documents is simple using the set keyword and JsonPath expressions.

* def myJson = { foo: 'bar' }

* set myJson.foo = 'world'

* match myJson == { foo: 'world' }

# add new keys. you can use pure JsonPath expressions (notice how this is different from the above)

* set myJson $.hey = 'ho'

* match myJson == { foo: 'world', hey: 'ho' }

# and even append to json arrays (or create them automatically)

* set myJson.zee[0] = 5

* match myJson == { foo: 'world', hey: 'ho', zee: [5] }

# nested json ? no problem

* set myJson.cat = { name: 'Billie' }

* match myJson == { foo: 'world', hey: 'ho', zee: [5], cat: { name: 'Billie' } }

# and for match - the order of keys does not matter

* match myJson == { cat: { name: 'Billie' }, hey: 'ho', foo: 'world', zee: [5] }

# you can ignore fields marked with '#ignore'

* match myJson == { cat: '#ignore', hey: 'ho', foo: 'world', zee: [5] }

XML and XPath works just like you’d expect.

* def cat = <cat><name>Billie</name></cat>

* set cat /cat/name = 'Jean'

* match cat / == <cat><name>Jean</name></cat>

# you can even set whole fragments of xml

* def xml = <foo><bar>baz</bar></foo>

* set xml/foo/bar = <hello>world</hello>

* match xml == <foo><bar><hello>world</hello></bar></foo>

Refer to the section on XPath Functions for examples of advanced XPath usage.

match and variables

In case you were wondering, variables (and even expressions) are supported on the right-hand-side. So you can compare 2 JSON (or XML) payloads if you wanted to:

* def foo = { hello: 'world', baz: 'ban' }

* def bar = { baz: 'ban', hello: 'world' }

* match foo == bar

remove

This is like the opposite of set if you need to remove keys or data elements from JSON or XML instances. You can even remove JSON array elements by index.

* def json = { foo: 'world', hey: 'ho', zee: [1, 2, 3] }

* remove json.hey

* match json == { foo: 'world', zee: [1, 2, 3] }

* remove json $.zee[1]

* match json == { foo: 'world', zee: [1, 3] }

remove works for XML elements as well:

* def xml = <foo><bar><hello>world</hello></bar></foo>

* remove xml/foo/bar/hello

* match xml == <foo><bar/></foo>

* remove xml /foo/bar

* match xml == <foo/>

Ignore or Validate

When expressing expected results (in JSON or XML) you can mark some fields to be ignored when the match (comparison) is performed. You can even use a regular-expression so that instead of checking for equality, Karate will just validate that the actual value conforms to the expected pattern.

This means that even when you have dynamic server-side generated values such as UUID-s and time-stamps appearing in the response, you can still assert that the full-payload matched in one step.

* def cat = { name: 'Billie', type: 'LOL', id: 'a9f7a56b-8d5c-455c-9d13-808461d17b91' }

* match cat == { name: '#ignore', type: '#regex [A-Z]{3}', id: '#uuid' }

# this will fail

# * match cat == { name: '#ignore', type: '#regex .{2}', id: '#uuid' }

The supported markers are the following:

| Marker | Description |

|---|---|

#ignore |

Skip comparison for this field |

#null |

Expects actual value to be null |

#notnull |

Expects actual value to be not-null |

#array |

Expects actual value to be a JSON array |

#object |

Expects actual value to be a JSON object |

#boolean |

Expects actual value to be a boolean true or false |

#number |

Expects actual value to be a number |

#string |

Expects actual value to be a string |

#uuid |

Expects actual (string) value to conform to the UUID format |

#regex STR |

Expects actual (string) value to match the regular-expression ‘STR’ (see examples above) |

#? EXPR |

Expects the JavaScript expression ‘EXPR’ to evaluate to true, see self-validation expressions below |

#[NUM] EXPR |

Advanced array validation, see schema validation |

#(EXPR) |

For completeness, embedded expressions belong in this list as well |

Optional Fields

If two cross-hatch # symbols are used as the prefix (for example: ##number), it means that the key is optional or that the value can be null.

* def foo = { bar: 'baz' }

* match foo == { bar: '#string', ban: '##string' }

Remove If Null

A very useful behavior when you combine the optional marker with an embedded expression is as follows: if the embedded expression evaluates to null - the JSON key (or XML element or attribute) will be deleted from the payload (the equivalent of remove).

* def data = { a: 'hello', b: null, c: null }

* def json = { foo: '#(data.a)', bar: '#(data.b)', baz: '##(data.c)' }

* match json == { foo: 'hello', bar: null }

‘Self’ Validation Expressions

The special ‘predicate’ marker #? EXPR in the table above is an interesting one. It is best explained via examples.

Observe how the value of the field being validated (or ‘self’) is injected into the ‘underscore’ expression variable: ‘_’

* def date = { month: 3 }

* match date == { month: '#? _ > 0 && _ < 13' }

What is even more interesting is that expressions can refer to variables:

* def date = { month: 3 }

* def min = 1

* def max = 12

* match date == { month: '#? _ >= min && _ <= max' }

And functions work as well ! You can imagine how you could evolve a nice set of utilities that validate all your domain objects.

* def date = { month: 3 }

* def isValidMonth = function(m) { return m >= 0 && m <= 12 }

* match date == { month: '#? isValidMonth(_)' }

Especially since strings can be easily coerced to numbers (and vice-versa) in Javascript, you can combine built-in validators with the self-valildation ‘predicate’ form like this: '#number? _ > 0'

# given this invalid input (string instead of number)

* def date = { month: '3' }

# this will pass

* match date == { month: '#? _ > 0' }

# but this 'combined form' will fail, which is what we want

# * match date == { month: '#number? _ > 0' }

You can actually refer to any JsonPath on the document via $ and perform cross-field or conditional validations ! This example uses contains and the #? ‘predicate’ syntax - and situations where this comes in useful will be apparent when we discuss match each.

Given def temperature = { celsius: 100, fahrenheit: 212 }

Then match temperature == { celsius: '#number', fahrenheit: '#? _ == $.celsius * 1.8 + 32' }

# when validation logic is an 'equality' check, an embedded expression works better

Then match temperature contains { fahrenheit: '#($.celsius * 1.8 + 32)' }

match for Text and Streams

# when the response is plain-text

Then match response == 'Health Check OK'

# when the response is a file (stream)

Then match response == read('test.pdf')

# incidentally, match and assert behave exactly the same way for strings

* def hello = 'Hello World!'

* match hello == 'Hello World!'

* assert hello == 'Hello World!'

Checking if a string is contained within another string is a very common need and match (name) contains works just like you’d expect:

* def hello = 'Hello World!'

* match hello contains 'World'

match header

Since asserting against header values in the response is a common task - match header has a special meaning. It short-cuts to the pre-defined variable responseHeaders and reduces some complexity - because strictly, HTTP headers are a ‘multi-valued map’ or a ‘map of lists’ - the Java-speak equivalent being Map<String, List<String>>.

# so after a http request

Then match header Content-Type == 'application/json'

# 'contains' works as well

Then match header Content-Type contains 'application'

Note the extra convenience where you don’t have to enclose the LHS key in quotes.

You can always directly access the variable called responseHeaders if you wanted to do more checks, but you typically won’t need to.

Matching Sub-Sets of JSON Keys and Arrays

match contains

JSON Keys

In some cases where the response JSON is wildly dynamic, you may want to only check for the existence of some keys. And match (name) contains is how you can do so:

* def foo = { bar: 1, baz: 'hello', ban: 'world' }

* match foo contains { bar: 1 }

* match foo contains { baz: 'hello' }

* match foo contains { bar:1, baz: 'hello' }

# this will fail

# * match foo == { bar:1, baz: 'hello' }

(not) !contains

It is sometimes useful to be able to check if a key-value-pair does not exist. This is possible by prefixing contains with a ! (with no space in between).

* def foo = { bar: 1, baz: 'hello', ban: 'world' }

* match foo !contains { bar: 2 }

* match foo !contains { huh: '#notnull' }

The ! (not) operator is especially useful for contains and JSON arrays.

* def foo = [1, 2, 3]

* match foo !contains 4

* match foo !contains [5, 6]

JSON Arrays

This is a good time to deep-dive into JsonPath, which is perfect for slicing and dicing JSON into manageable chunks. It is worth taking a few minutes to go through the documentation and examples here: JsonPath Examples.

Here are some example assertions performed while scraping a list of child elements out of the JSON below. Observe how you can match the result of a JsonPath expression with your expected data.

Given def cat =

"""

{

name: 'Billie',

kittens: [

{ id: 23, name: 'Bob' },

{ id: 42, name: 'Wild' }

]

}

"""

# normal 'equality' match. note the wildcard '*' in the JsonPath (returns an array)

Then match cat.kittens[*].id == [23, 42]

# when inspecting a json array, 'contains' just checks if the expected items exist

# and the size and order of the actual array does not matter

Then match cat.kittens[*].id contains 23

Then match cat.kittens[*].id contains [42]

Then match cat.kittens[*].id contains [23, 42]

Then match cat.kittens[*].id contains [42, 23]

# and yes, you can assert against nested objects within JSON arrays !

Then match cat.kittens contains [{ id: 42, name: 'Wild' }, { id: 23, name: 'Bob' }]

# ... and even ignore fields at the same time !

Then match cat.kittens contains { id: 42, name: '#string' }

It is worth mentioning that to do the equivalent of the last line in Java, you would typically have to traverse 2 Java Objects, one of which is within a list, and you would have to check for nulls as well.

When you use Karate, all your data assertions can be done in pure JSON and without needing a thick forest of companion Java objects. And when you read your JSON objects from (re-usable) files, even complex response payload assertions can be accomplished in just a single line of Karate-script.

Refer to this case study for how dramatic the reduction of lines of code can be.

match contains only

For those cases where you need to assert that all array elements are present but in any order you can do this:

* def data = { foo: [1, 2, 3] }

* match data.foo contains 1

* match data.foo contains [2]

* match data.foo contains [3, 2]

* match data.foo contains only [3, 2, 1]

* match data.foo contains only [2, 3, 1]

# this will fail

# * match data.foo contains only [2, 3]

Validate every element in a JSON array

match each

The match keyword can be made to iterate over all elements in a JSON array using the each modifier. Here’s how it works:

* def data = { foo: [{ bar: 1, baz: 'a' }, { bar: 2, baz: 'b' }, { bar: 3, baz: 'c' }]}

* match each data.foo == { bar: '#number', baz: '#string' }

# and you can use 'contains' the way you'd expect

* match each data.foo contains { bar: '#number' }

* match each data.foo contains { bar: '#? _ != 4' }

# some more examples of validation macros

* match each data.foo contains { baz: "#? _ != 'z'" }

* def isAbc = function(x) { return x == 'a' || x == 'b' || x == 'c' }

* match each data.foo contains { baz: '#? isAbc(_)' }

Here is a contrived example that uses match each, contains and the #? ‘predicate’ marker to validate that the value of totalPrice is always equal to the roomPrice of the first item in the roomInformation array.

Given def json =

"""

{

"hotels": [

{ "roomInformation": [{ "roomPrice": 618.4 }], "totalPrice": 618.4 },

{ "roomInformation": [{ "roomPrice": 679.79}], "totalPrice": 679.79 }

]

}

"""

Then match each json.hotels contains { totalPrice: '#? _ == $.roomInformation[0].roomPrice' }

# when validation logic is an 'equality' check, an embedded expression works better

Then match each json.hotels contains { totalPrice: '#($.roomInformation[0].roomPrice)' }

There is a shortcut for match each explained in the next section that can be quite useful, especially for ‘in-line’ schema-like validations.

Schema Validation